Geophagus sp. “Orange Head Tapajos”, a popular endemic fish at risk due to yet another unpopular Brazilian Dam project? Image by Matt Pedersen

With all the doom and gloom out there lately, I admit, it’s tough to keep up. For aquarists interested in rare and exciting Loricarids, Brazil’s Belo Monte Dam captured our attention, the forecasted extinctions a huge hydroelectric project would cause are now probably on their way to foregone conclusions. With Belo Monte’s first turbine reportedly starting to generate electricity on April 20th, 2016, the world can now only sit and watch the changes and damage unfold. (See Michael Tuccinardi’s report, Xingu Rising, from the May/June 2016 AMAZONAS.)

Meanwhile, here in the US, my sportfishing background has me uniquely aware of efforts being made to remove dams, both large and small, on waterways around the country. Dam removal can be hotly contested, as is the ongoing debate over the repair vs. removal of a currently inactive recreational dam in Milwaukee, WI. It seems that restoring the natural flows of our waterways is at the center of species restoration efforts, allowing natural fish migrations to renew themselves, correcting the mistakes of our forefathers and generally allowing nature to “heal.”

Yet despite all the evidence that dams are often not the “environmentally friendly” solutions to energy production and needs (they seem to come at great environmental cost), they keep being built. But it would seem that not all dams are necessarily created equal? I’m actually a beneficiary of hydroelectric power here in Duluth, MN. It turns out that 5 hydroelectric dams on the St. Louis River in this region produce a total of 92.1 Megawatts; hydroelectric power may well be running my fishroom as I sit and type this tonight. No one here talks about extinct native species or removing these dams. No one is up in arms about the displacement of people from their homes.

But perhaps my view is tainted by shifting baselines; centuries of industrial ravage in the region, including mining and timber harvest, have forever changed the landscape around the whole of Lake Superior. The dams were built before my parents were born. The indigenous people of the region, the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, who once called the St. Louis River corridor their home, are apparently now relegated to the Fon du Lac Indian Reservation, whose northeast border is a small portion of the St. Louis River watershed.

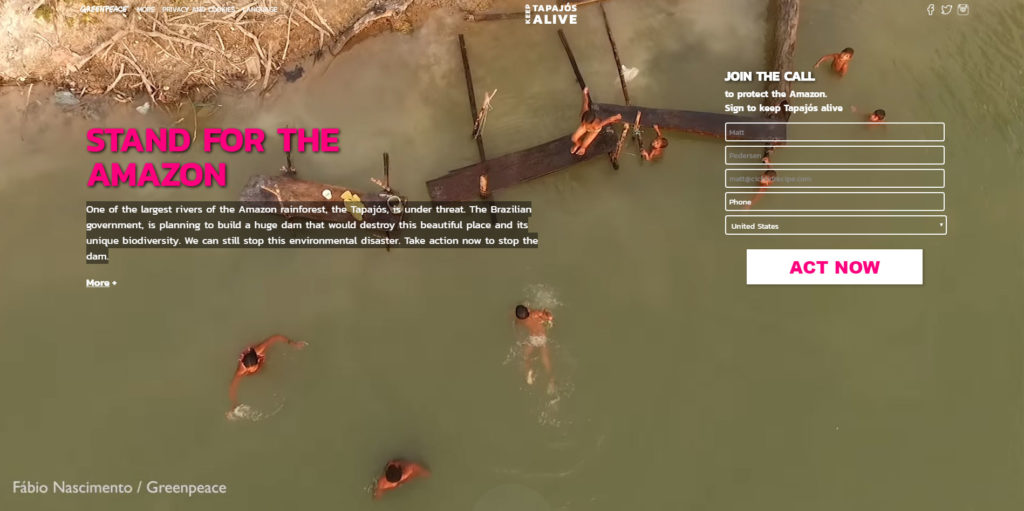

So when I learned today that there’s a lot more going on in Brazil than simply Belo Monte, I had to do some quick investigation. The next posterchild in Brazil’s damning of the Amazon is the São Luiz do Tapajós Dam (Tapajos Dam), part of a planned multi-dam Tapajos hydroelectric complex. It seems Greenpeace is currently pushing out the news through a growing campaign of Free Tapajos / Keep Tapajos Alive. The website Tapajos.org gives a very cursory view of the issue.

Screenshot of Tapajos.org

![Rio Tapajos in Brazil - By Kmusser [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.amazonasmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Tapajosrivermap.png)

Rio Tapajos in Brazil – By Kmusser, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

According to Greenpeace, São Luiz do Tapajós is slated to be the largest among a whopping 40 total new dams planed for the Tapajós river basin. Tapajos Dam will be the second largest in the country, behind only Belo Monte; it said it will generate 8040 Megawatts (MW) of electricity (puts the 92.1 from five dams here in Duluth, MN in a bit of perspective).

The story of the Tapajos Dam should sound pretty familiar…once again indigenous people, this time the Munduruku, stand to lose their land underneath the floodwaters of the dam reservoirs. Greenpeace Brazil has worked to bring the plight of these people to broader attention.

Greenpeace activists and Munduruku Indians use stones to form the Tapajós Free phrase on a sandy beach on the banks of the eponymous river, near the city of Itaituba, in Pará. The protest, which was attended by about 60 Mundurukú, occurred in the region where the government plans to build the first of a series of five dams in the Tapajós basin. (Photo Greenpeace / Marizilda Cruppe 11/26/2014) – CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

Greenpeace activists and Munduruku Indians use stones to form the Tapajós Free phrase on a sandy beach on the banks of the eponymous river, near the city of Itaituba, in Pará. The protest, which was attended by about 60 Mundurukú, occurred in the region where the government plans to build the first of a series of five dams in the Tapajós basin. (Photo Greenpeace / Marizilda Cruppe 11/26/2014) – CC BY 2.0 via Flickr

This video from AmazonWatch presents the plight of the Manduruku.

Again, like with Belo Monte, corruption and dubious practices seem to be at play, including what some have called “cosmetic” environmental impact statements. This time, once again, we don’t know what’s at stake from a biodiversity standpoint (plenty of taxonomic work is still being done in the region, such as the recently described Geophagus mirabilis from the rio Aripuanã, a Tapajos tributary). We do know that multiple conservation parks will be sacrificed to the floodwaters. This time, yet again, the first beneficiaries of whatever power is produced seem to be mining operations.

Among my fellow AMAZONAS editors, I could only describe the mood as battle-weary cynical optimism. Mike Tuccinardi tipped me off that the license for the Tapajos Dam was “just suspended” (on April 20th, 2016). Stephan Tanner noted that with Brazil’s corruption issues becoming more public, perhaps this could “indeed signal a positive change that the country might eventually come away better.”

I’m hard pressed to indulge in this hope, given that one dam out of 40 would still leaves a lot to contend with. And with new dams coming online in the past years (for example the Jirau Dam built on the Madeira River in 2012, a name I recognize for its Discus), and knowing that Tapajos is just one dam in an entire series of dams designed to regulate riverflows and insure stable, consistent water supplies, something tells me that these other dams upriver might just get built anyway.

Will Brazilians 50 years from now look back on Belo Monte and a possible Tapajos Dam as the status quo? Will they even know of the Munduruku? Will they talk about these potentially disenfranchised peoples in the same nonchalant manner that I look up the Ojibwe of the Lake Superior region so I can throw out a few random facts about how their land was lost to “progress”?

For the moment, the São Luiz do Tapajós Dam possibly represents the next battle in Brazil’s damning of the Amazon. But we must know, now, that it is just one of many battlefronts in Brazil’s larger, systemic plan to harness the resources at its disposal. If someone sitting here, writing from a warm five-bedroom home in North America, is about to lecture the government of another country to not “repeat our own mistakes,” perhaps they need to be shown a different path forward. Otherwise, perhaps this too, is in the end, a foregone conclusion, which leaves us, the aquarists, not that much time to figure out what we can do, in our own small ways, to preserve whatever special biodiversity is about to be lost, again.

Additional Reading

Greenpeace’s Keep Tapajos Live website – Tapajos.org

The Amazon’s Tapajos Basin is in danger – http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/news/Blogs/makingwaves/amazon-tapajos-basin-megadam/blog/54266/

Greenpeace joins the Munduruku to protest damming of the Tapajos- http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/press/releases/2016/Greenpeace-joins-the-Munduruku-to-protest-damming-of-the-Tapajos/

International Rivers – Tapajós Basin Dams – https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/tapaj%C3%B3s-basin-dams-3352

International Rivers – Tapajos Basin – https://www.internationalrivers.org/campaigns/tapaj%C3%B3s-basin

Greenpeace Energy Desk – Q&A: Brazil’s giant new Amazon dam-building project and why it matters – http://energydesk.greenpeace.org/2016/02/11/qa-what-are-the-impacts-of-building-hydroelectric-dams-in-the-amazon/

National Geographic – Amazon Dams Keep the Lights On But Could Hurt Fish, Forests – http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/04/150419-amazon-dams-hydroelectric-deforestation-rivers-brazil-peru/

Americas Quarterly – Why Amazon Tribes Are Losing the Fight Against New Dams – Again – http://www.americasquarterly.org/content/why-amazon-tribes-are-losing-fight-against-new-dams-again

Dams-Info.org – São Luiz do Tapajós Dam Profile – http://dams-info.org/en/dams/view/sao-luiz-do-tapajos/

Amazon Watch – Battle for the Tapajós: Brazil’s Construction of Hydroelectric Dams Threatens the Munduruku People – http://amazonwatch.org/news/2015/0109-battle-for-the-tapajos

Seriously Fish – Geophagus sp. “Orange Head” – http://www.seriouslyfish.com/species/geophagus-sp-orange-head/

A new colorful species of Geophagus (Teleostei: Cichlidae), endemic to the rio Aripuanã in the Amazon basin of Brazil – http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1679-62252014000400737

Trackbacks/Pingbacks