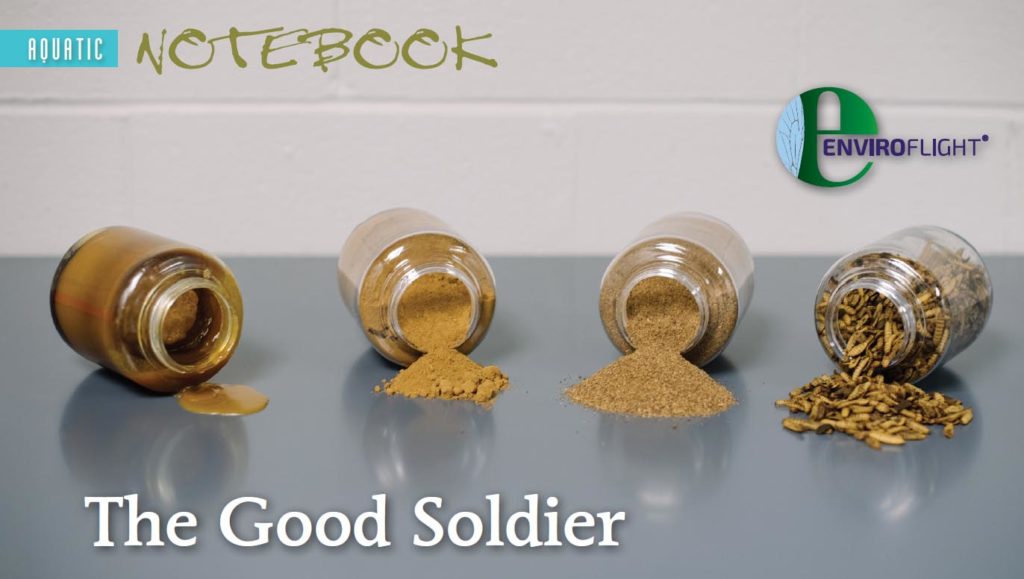

EnviroProducts™ made from the Black Soldier Fly (left to right): oil, meal, frass, and dried larvae. Frass, the waste product, is used for natural fertilizer

A special excerpt from AMAZONAS Magazine, July/August 2019, by Gary Elson

An excerpt from the July/August 2019 issue of AMAZONAS Magazine, NATURALLY NATIVES. Click to buy the back issue.

Black Soldier Fly larvae are being touted as a miracle food of the future for pets as well as humans. For now, however, they are an innovative, high-quality food for fish and other animals.

When early aquarists compared what fish eat in nature with the limited foods available in the nascent hobby, they began looking back to nature. They conducted live-food collecting parties in springtime, hunting for daphnia, copepods, and mosquito larvae. The brine shrimp cyst industry was born, with the tiny food collected from Utahan, Californian, Chinese, Canadian, and Russian lakes and bays. Laboratories produced wingless fruit flies.

Over time, the quality and selection of prepared fish foods has skyrocketed, but serious aquarists, especially those who intend to breed their fish, are never satisfied. Flake and pellet of varying quality are fine for growth and display, but for many species they don’t always provide what’s needed for breeding. Plant eaters have always been fairly easy to feed, but insect-eaters have traditionally been more difficult and expensive to accommodate. Alternative protein sources, such as costly frozen foods, freeze-dried bugs (less appealing and nutritious after processing), lean heart muscle from goats or cows, or chopped up earthworms just haven’t done the job. Most aquarists are unprepared to culture bugs at home, and if we do, they are often too large for small insectivorous fishes.

Development of Black Soldier Fly Larvae

Almost 20 years ago, while seeking alternative protein sources, Allen Repashy found the Black Soldier Fly Larvae (BSFL, Hermetia illucens). As many scientifically inclined vivarists do, Repashy was scouring the web for scientific papers. While looking for a better feeder insect, he stumbled upon a 1994 scientific publication called “A value-added manure management system using the black soldier fly” by Dr. Craig Sheppard.

In his article, Sheppard described the nutritional value of the BSFL and Repashy noted its potential, particularly the high calcium levels and calcium/phosphorus ratio. For a reptile breeder, these are crucial values, and finding it in a natural insect could prove to be very useful to fish- and herp-keepers.

Repashy contacted Dr. Sheppard and proposed the idea that these insects and larvae would make excellent feeders for reptiles, fishes, and other insectivores, if they could be commercially raised as a hygienic food source. Dr. Sheppard responded with enthusiasm, because he had a personal history of commercially raising mealworms and understood the market potential of these flies. Their communication led to the construction of a pilot plant at Dr. Sheppard’s property, and feeding trials at Repashy’s breeding facility. The new food showed intriguing potential.

Dr. Sheppard’s company became the first commercial facility in the world to produce black soldier fly larvae, commercially known as Phoenix Worms. A few years later, after promoting these new feeder insects, they quickly became an invaluable alternate food for exotics.

With his well-respected background in the reptile food industry, Repashy also quickly saw the potential for BSFL to be processed into a meal that could be used in his Repashy Superfoods gel formulations. While the larvae were easy to raise, breeding the flies and collecting eggs in huge numbers and under sanitary conditions were challenging. At the time, the economies of scale and production systems just didn’t exist to economically produce such a product.

It took another 10 years, but one day, Repashy was contacted by John Gramieri, who was the Mammal Curator at the San Antonio Zoo and the chairman of the American Zoo and Aquarium Association’s PAX TAG (Pangolin, Aardvark, and Xenarthran [anteaters, tree sloths, and armadillos] Taxon Advisory Group), about helping with a diet formulation he was using at the zoo for these little-understood species. Gramieri mentioned to Repashy that he was getting small amounts of dried BSFL from a place called EnviroFlight in Ohio, for his formula, and passed on the contact information.

Repashy quickly reached out to EnviroFlight and its mastermind Glen Courtright to discuss BSFL availability. They were successfully producing dried larvae (Enviro-Bug), but had yet to develop a way to produce a fine grain meal due to the fat content of the larvae. Collaborative brainstorming led to the construction of the first pilot plant to produce a clean and green BSFL meal. It was the first such plant in the world, although certainly not the last. Within two years, Repashy’s gel Superfoods was EnviroFlight’s first commercial customer for BSFL insect meal, EnviroMeal, which provided a catalyst for BSFL meal uses in other areas.

Now in 2019, BSFL production facilities are popping up throughout North America, Europe, and Asia motivated by the animal feed possibilities. The product has been recognized as a real breakthrough for its ability to reduce the demand for other, more environmentally demanding, protein sources such as fish meal.

BSFL as Fish Food

A small innovative idea has grown into a large improvement in fish and reptile nutrition. Repashy has successfully marketed high-quality soldier fly-based gel foods for more than six years now, and several competitors have introduced extruded BSFL feeds. There is a strong marketing push behind BSFL foods and hobbyist experiences are positive. They report that even finicky species of fish that usually will not eat dried or prepared foods will often attack soldier fly foods with no reserve, and color development also seems excellent.

Breeding success is a key indicator of food quality for aquarists. Fish don’t reproduce on subpar foods. Although many easily bred fish will respond to non-insect-meal-based commercial foods, the more challenging species require live food or an equal equivalent. Many picky fish, which don’t even bother to taste traditional flake or pellet foods, not only eat BSFL foods but will breed on a diet of BSFL-based pellets and gel. Commercial foods can’t completely replace live foods, but in the absence of live foods, there’s a reliable alternative.

A thriving industry has grown up around BSFL in the years since Dr. Sheppard’s work—one that aims to take what Repashy noted and move it from our fish tanks and into our own food chain. As an alternative protein source, BSFL may become prominent not only in our animal feed, but on our own plates, as well. We’ll no doubt see how that project plays out over the next few years.

References

Sheppard, D. C., G. L. Newton, S. A. Thompson and S. E. Savage. 1994. A value added manure management system using the Black Soldier Fly. Bioresource Technology. 50: 275–279.