When my last blog post (VIDEO: Details of Betta macrostoma mating and breeding) was published, I got a comment asking whether I had ever tried incubating the eggs artificially. It is a common practice among African cichlid keepers since many of the African cichlids are mouthbrooders. Since Betta macrostoma have a similar way of incubating eggs, artificial incubation of eggs seems plausible. I personally had never tried this, as I pointed out in the comment. However, the question sparked my curiosity. I couldn’t help but think that theoretically this makes sense and seems doable. Well, I took a mental note of it and moved on.

Bad Males?

As I mentioned in my previous blog post, keepers of Betta macrostoma are often lugubrious over the fact that their males don’t hold the eggs to term. My last blog post encouraged some experienced Betta macrostoma breeders to open up to me and share their experiences and opinions.

But why do male Betta macrostoma fail to hold eggs to term, incubating their offspring successfully? Before we move on to discussing the artificial incubation, it’s important to understand the possible hypotheses behind what leads to the male eating the eggs. The following are some of the possible explanations that I have heard and/or experienced myself. Full disclosure—these are just experiences and theories. A lot of research would be required to prove these claims as facts.

Cause #1 – Young Age

Young males (many experienced betta keepers call a male smaller than 3 inches a young male) are considered to not possess enough willpower and energy to hold to term, but it is considered crucial that they try. This shows that the male is willing and has the ability to spawn and work with the female to get the eggs in his buccal cavity.

I recently had a 7-month-old male, which is about 2.5 inches in length, spawn with a very experienced and “older than him” female. Considering his young age, his buccal cavity is smaller in comparison to adult males I have. This young male had to call it quits while the female still had many eggs left to lay. The female kept trying to convince him to continue by performing the typical serpentine-like dance, but he would not budge. He held the eggs for the next three days before spitting them all out on the third day. Upon inspection, I noticed that many of the eggs were fertile. I think he just didn’t have enough will power to hold to term.

Causes #2 and #3 – Hunger or Stress Inducing Event

According to this theory, if the male gets too hungry during the incubation period, he will end up eating the eggs to satiate his hunger. Logically, this claim makes sense. Any animal can get hungry enough to make such regrettable decisions. The question that drives me nuts is how can you prove if a certain Betta macrostoma male ate the eggs because he was hungry and not because of another reason?

This brings me to the next theory, where a stress-inducing event such as loud noise, bang, a flash of light, etc. is known to spook the male, ultimately leading to the male eating the eggs. I myself am guilty of covering the tank from all sides when the male is incubating in the hope of preventing the male from ingesting the eggs. Many hobbyists rely on dark tinted water to keep the visibility low. The conflict around this theory is that usually when an egg-incubating Betta macrsotoma male is spooked, he spits the eggs out rather than ingesting them. I personally have experienced this while stripping the male of the eggs. As I tried to catch the male in the net, he let many eggs out.

Cause #4 – Water Chemistry

This theory involves water chemistry and takes the chemical composition of water into consideration. Is it possible that the water is lacking an element or a compound that allows for better fertilization of eggs?

Without going into too much detail, many research projects have been conducted to understand the transportation of human sperm in the female reproductive tract and how the vaginal pH controls the fertility rate in humans. It is not impossible that a similar phenomenon takes place during underwater external fertilization where water chemistry dictates the rate of fertilization.

However, this theory loses its weight when a hobbyist who has multiple Betta macrostoma pairs claims that only one or two males eat their eggs while the rest of the males continue to hold to term. These hobbyists use water from the same source in all their tanks. Water chemistry likely won’t be drastically different among tanks in the same fishroom, thus failing to account for the improper fertilization.

Cause #5 – Too Many Eggs, Not Enough Sperm?

Is it possible that some males struggle with fertilizing the eggs properly? It’s not unheard of in other animal species. Why would fish be indifferent? Maybe?

Cause #6 – Lacking Experience

This is the point that makes the most sense to me. Betta macrostoma breeding can continue for hours. Unlike Betta splendens, not every embrace in Betta macrostoma yields good results. If the male is not doing his best to focus and work with the female, it is very easy for the female to release the eggs but the male to not be in the best position during the embrace to properly fertilize the eggs. The female does her job of picking up the eggs and transferring them to the male, but if the eggs were not fertilized properly, they will spoil in two days and then the male will have no other option than just ingesting them.

An Opportunity To Experiment

During a daily inspection in the fishroom, I noticed that one of the Betta macrostoma males I have was holding eggs. This particular male had just released a batch of eggs about 6 days before holding again. I was worried that this male hadn’t regained enough strength to pull through another 15-day incubation period. I usually like to give them at least 15 days or more, if possible, before the male starts holding again. I try to keep the male and the female separate for 10 days after the male has released the eggs.

But this time, I had introduced the female earlier than usual, and within a day of introducing the female, the pair had spawned. I posted my dilemma on a Facebook group where a dear friend and a master Betta macrostoma breeder suggested that I strip the male and try incubating the eggs artificially. This was just the motivation I was looking for. I asked my lovely wife to hold the camera while I went to catch the Betta macrostoma male from the tank. I had a Lee’s specimen container filled with the water from the same tank where the fish were in, ready to receive the eggs.

Stripping Eggs From The Male

As I was about to approach the tank to catch the Betta macrostoma male, I was thinking to myself that the male would probably ingest the eggs as soon as I tried to net him. I used a very soft silk net to catch the male. As I was trying to get him into the net, he let a few eggs out of his mouth. The female, which was also present in the tank, rushed to collect the falling eggs. I didn’t see her hold them in her mouth though, which means that she ended up eating those eggs. If I were to do this again, I will make sure to take the female out first.

Once the male was in the net, I gently held him with my left hand and walked a few steps to the table that had the Lee’s specimen container. Learning from my previous mistakes, this time I made sure that instead of using my nails, I used a soft but flat object to open the fish’s mouth—a soft piece of foam. Once his mouth was open, I dipped the fish in and out of the water a few times. This made a lot of the eggs fall out. Once I was certain that no more eggs were left in the male’s buccal cavity, I placed the male back in the tank.

Egg Development and Hatching

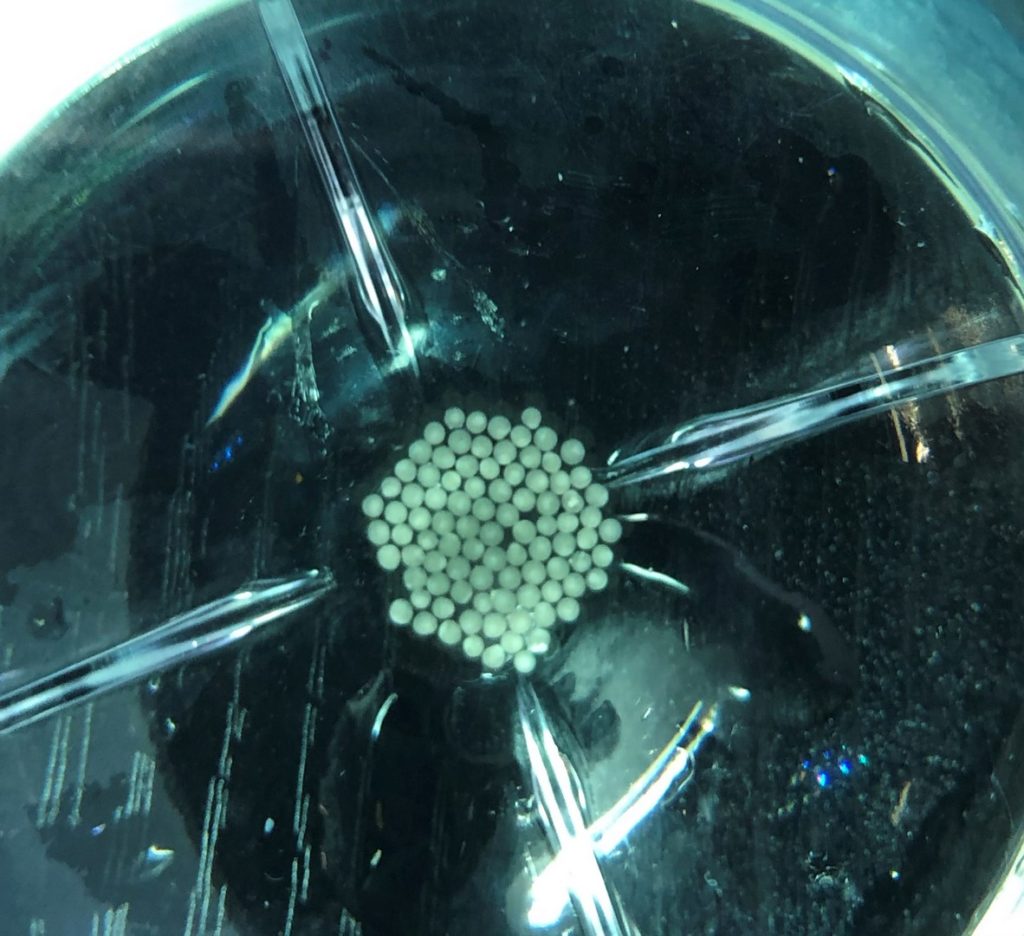

I now had a lot of eggs in the Lee’s specimen container. I took out my Cobalt egg tumbler, connected it to an air supply and put the eggs in the tumbler. I had a very “gentle” flow going for the first two days as I watched the eggs tumble in the tumbler.

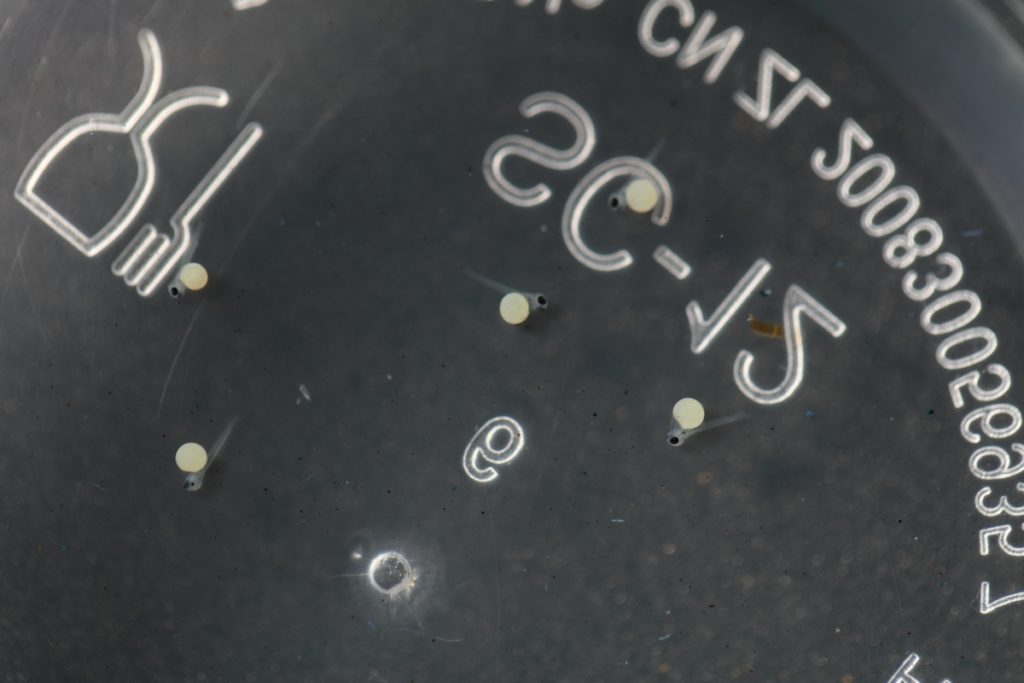

On day 3, I noticed some eggs that had fungus. I took out the tumbler and removed spoiled eggs. Usually, eggs that weren’t fertilized start to go bad, and fungus takes over. This fungus, however, sometimes can also attack the nearby good, fertilized eggs. Breeders usually use methylene blue to keep the fungus in check. Keeping that in mind, I also added a few drops of Kordon Methylene Blue in the tank.

As I kept taking out unfertilized, fungused eggs, I noticed two things-

- Unfertilized bad eggs don’t maintain their shape after a couple of days. When I tried to remove them using a pipette, they behaved more like runny gel than a solid mass. So, it’s possible that they simply “melt” in the male’s mouth while he is incubating leaving only fertilized, good eggs.

- Like in many other species of fish, unfertilized eggs start to take on a different color than fertilized eggs. They start looking relatively white in color as time passes whereas the fertilized eggs look more off-white, almost yellowish in color.

As day 5 came, I still couldn’t see any signs of hatching occurring. This debunked the point I had made in my previous blog post about the eggs hatching in 2 to 3 days. But then how do we explain the decrease in the protrusion of the male’s buccal cavity after 3 days? One plausible explanation can be that by day 3 almost all the unfertilized eggs have been ingested by the male and the fertilized eggs that are left don’t make his mouth look so big as they did on day 1 of holding.

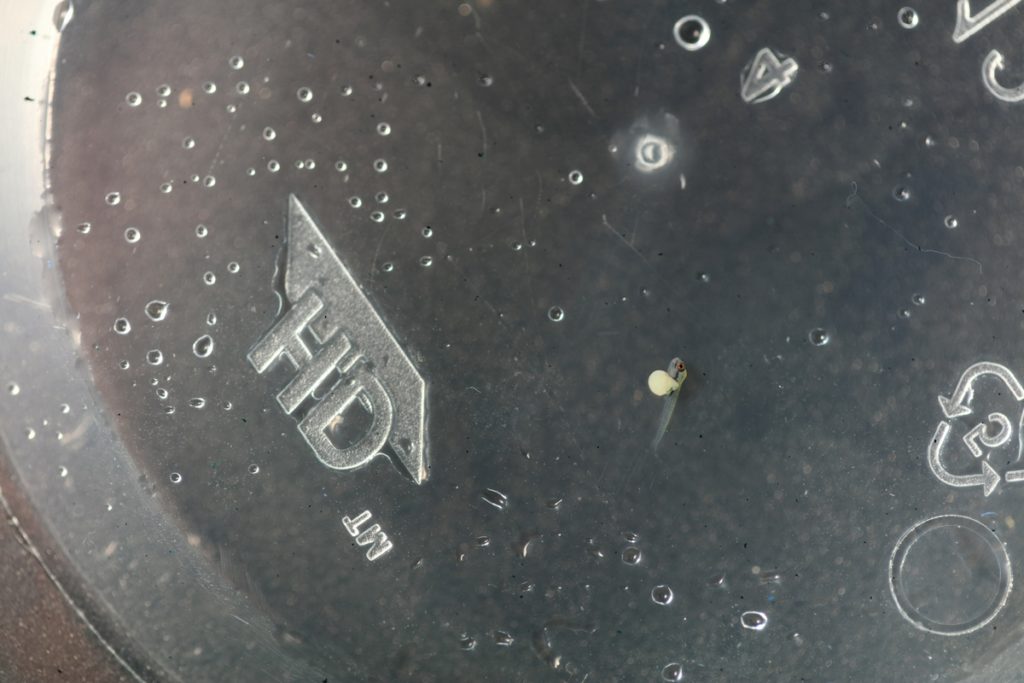

On day 6 however, I could see little tails on most of the eggs. I had approximately 13 eggs that hatched by day 7. This is where I made a mistake. After taking progress photos on day 7, when I turned on the tumbler again, I increased the airflow a little bit. I am not entirely sure how it affected the fry, but I lost at least 5 fry that night. The next day upon noticing this, I decreased the airflow and those 8 fry made it to the second week of incubation. “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”- by going off this motto, I left the fry at the same airflow for the next week.

Development of Fry: The Free-Swimming Stage

On day 13, I could see some of the fry swimming up in the water column inside the tumbler. When I took them out to take progress photos, I could see the last bit of the yolk sack remaining to be consumed on the fry. On day 13, I was left with 7 fry. They were able to move in the water but would settle down on the bottom of the container. It is possible that this movement of fry in the male’s buccal cavity can be one of the catalysts when it comes to him releasing the fry.

I let the fry spend one more day in the tumbler and on day 14, I pulled them out and have started treating them as I would treat fry from any other batch that was incubated by a Betta macrostoma male.

As of today, all 7 of the fry are alive and continue to thrive on baby brine shrimp or freshly hatched Artemia nauplii.

I hope that this report motivates more hobbyists to take interest in wild Betta species and convinces them to learn more about these beautiful fishes.

References

Fabiana Y. Nakano1; Rogério de Barros F. Leão2; Sandro C. Esteves1 Insights into the role of cervical mucus and vaginal pH in unexplained infertility

http://www.dx.doi.org/10.5935/MedicalExpress.2015.02.07

Trackbacks/Pingbacks